Much like the long-running saga of Japan’s integrated resorts, authorities in Thailand are again looking into the possibility of legalizing casinos. But is it all just a pipe dream? IAG takes a closer look at what the future may hold.

Aside from the Muslim-majority nations of Indonesia and Brunei, Thailand is the only ASEAN nation without a legal casino and yet it maintains strong connections to gambling. With a population of almost 70 million, it has been estimated that as much as half of its adult population gambles via illegal means such as sports betting – more than THB160 billion (US$5 billion) bet is wagered on football alone each year – or the many underground casinos that permeate major metropolitan centers.

Thailand has long been viewed as an attractive candidate to one day establish a legal casino industry.

There is certainly demand.

Vitaly Umansky

Explains; Vitaly Umansky, Managing Director & Senior Analyst – Global Gaming for asset management firm AB Bernstein

There are obviously a bunch of gaming customers from Thailand that gamble all over the place. Poipet in Cambodia is a clear example of this, which is almost entirely Thai customers.

Vitaly Umansky

But, Umansky asks, is it all hopes and dreams?

This is the question currently facing the Thai parliament, which in early December voted to set up an extraordinary committee to examine a proposal to open an integrated resort with a casino, with the goal of attracting more foreign visitation and boosting the local economy.

- Suggested read: Pansy Ho announced an idea driven by one country, two systems.

The extraordinary committee is said to comprise 60 members of which 15 are cabinet representatives with the other 45 from various political parties. According to The Bangkok Post, the committee will examine the legal amendments required to legalize casino gaming as well as the social and economic impact of IRs in other jurisdictions. A report could be completed as early as this month.

Sources Inside Asian Gaming spoke, however, questioned the motives, both behind the establishment of such a committee right now and of those involved. For example, one senator closely linked to the committee is widely alleged to be the “godfather” of illegal gambling in Bangkok, suggesting a clear conflict of interest.

If local media reports are to be believed, this latest push for legalized casino gambling in Thailand is at least in part a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha said to be concerned that illegal gambling dens had become super spreader venues. As a result, Prayut is apparently open to holding public discussions on the pros and cons of legalizing gambling despite being opposed to the idea himself.

Deputy Prime Minister Gen. Prawit Wongsuwan also noted in January that the absence of casinos in Thailand was no deterrent to its citizens’ gambling.

Look at the countries around us,” he said. “Our people visit those casinos too.

Deputy Prime Minister Gen. Prawit Wongsuwan

Despite Prime Minister Prayut launching a crackdown on underground casinos – shortly after claiming the leadership by way of a military coup in 2014 – which sources say eliminated up to 80% of those in operation at the time, a government panel established in February 2021 found there were still around 200 illegal gambling dens operating nationwide, including 47 in the Bangkok metropolitan area.

Yet talk of legalizing casinos in Thailand is nothing new

It was even somewhat close to becoming a reality back in 2003, when then-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra went as far as meeting with representatives of US casino giant MGM Resorts, or MGM Mirage as it was known at the time. Rather than navigate the difficult path of passing a specific casino law, Thaksin had recognized that simply amending the current Gambling Act of 1935

- which allows for betting on a small number of select activities such as horse racing, cockfighting, combat sports and the lottery

- to include casinos was a more realistic path forward. He was likely correct, but more pressing matters would ultimately consume Thaksin’s time before he fell victim to an earlier military coup in 2006.

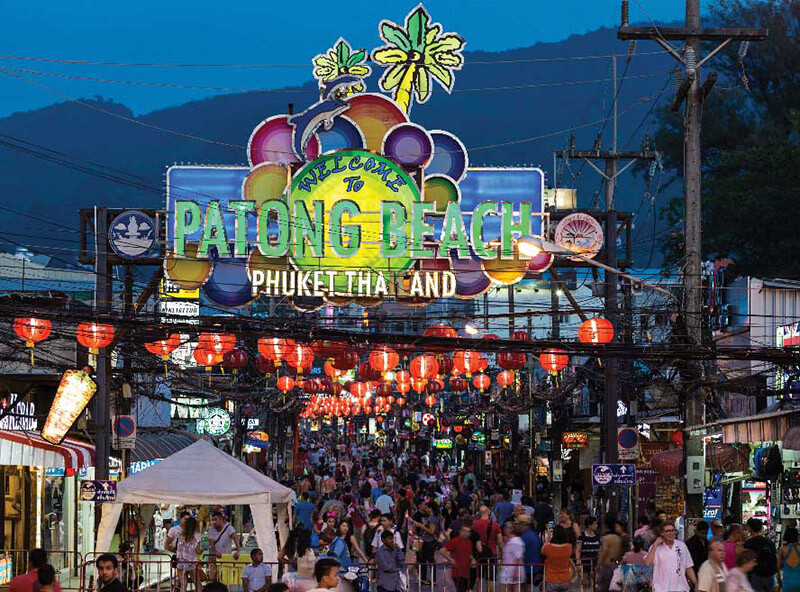

In 2008, newly appointed Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej promised to open casinos in five major tourist centers – Pattaya, Phuket, Khon Kaen, Chiang Mai, and Hat Yai – if he served out his full four-year term.

We have to seriously study the idea of how to open legal casinos,” he said. This way, the illegal dens and private casinos will close down. If people want to gamble they can come here, so the police won’t have to crack down on [the illegal dens].

Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej

In the end, Samak didn’t last four months, let alone four years, being sentenced to two years in jail on an old libel charge and fleeing to the United States.

What separates Thailand’s latest attempt to legalize casino gaming from those previous efforts – and gives some hope to proponents – is the monarchy. King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who held the throne for almost 70 years until his death at the age of 88 in October 2016, was famously anti-gambling, while his son and successor, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, is said to be intrigued by the idea of bringing to Thailand the type of multi-billion dollar integrated resorts seen in Macau and Singapore.

Certainly, there is some merit to the notion

A feasibility study conducted by an internationally renowned consultancy, pre-COVID-19, recommended the development of “two or three” casinos in Thailand, comprising a large-scale integrated resort in Bangkok and two smaller satellite casinos in tourist destinations.

Assuming investment levels of up to US$4 billion for the Bangkok IR – smaller for the satellite locations – the study estimated annual gross gaming revenues of between US$4 billion and US$4.7 billion for the three properties combined. That would rank right alongside Singapore, whose two hugely successful integrated resorts, Marina Bay Sands (MBS) and Resorts World Sentosa (RWS), generated a combined GGR of US$4.51 billion in 2019.

Umansky, however, is wary of such comparisons.

“Singapore, when they legalized casinos, had a very clear objective of what they wanted to achieve,” he says. “It was crystal clear what they wanted, they ran a very good process, they had outlined parameters, it was highly legalistic, the industry is well regulated – they had an objective. “The Singapore model was to build a giant family amusement leisure destination for long-term visitation (RWS), and a massive convention-based, city-oriented property to bring in international business travelers (MBS), and in both cases gaming supports the development of all that.

“But in Thailand, the question is ‘Why you would want to do this?’ Thailand is already a massive tourist destination, so what are you trying to achieve? Giving locals somewhere to gamble so they don’t do it overseas? If that’s the objective you put [the IR] in Bangkok. If that’s not the goal you put it in Phuket or Pattaya, but those beachfront casino resorts rarely work because the people that attend those locations don’t want to do a whole heap of gambling. The people that want to spend six hours on the beach are not the same people that want to spend six hours in a casino like in Macau.

So we need to know what the government would want to achieve before we start considering where it makes sense to [put legalized casinos], because where it makes sense to have one is based on what it is you’re trying to achieve.

Umansky

Umansky is also highly dubious of aligning the desires of Thai authorities with those of operators, particularly if banning locals were to become part of the agenda.

“Foreigner-only doesn’t work,” he says, pointing to the troubles COVID has created for Korea’s foreigner-only casino industry.

“I mean sure, you can do a US$200 million property in Phuket and that will make a lot of money, but that’s not what the government is going to allow. They’re going to want you to build a US$5 billion property catering only to foreigners and with an absurd tax rate – and none of it will ever pan out.”

Others aren’t so sure. According to sources who spoke to IAG on condition of anonymity, Thailand is more likely to follow the lead of Singapore and Japan by introducing an entry fee in the realm of THB500 TO THB1,000 baht (US$15 to US$30) in an effort to exclude those who can’t afford to gamble.

“The market could be quite big,” one source said. “Thailand had 13 million Chinese visitors in 2019 and that was on an upward trajectory. Chinese people love coming to Thailand, so that’s huge. You’ve also got a lot of Thai people who go to Singapore, Macau, Europe, America, and Australia to gamble. So there is a market there for sure, supplemented by a huge Chinese market.”

Based on the feasibility study referenced previously, legalized casinos if open to all would attract an estimated 55/45 split of international visitors versus locals.

Outside of Bangkok and Phuket, Pattaya is also mentioned as an obvious location. It was here that authorities had proposed opening an IR back in 2002 on the site of the Imperial Pattaya Hotel in Chon Buri.

“It makes even more sense today because it’s only an hour from the international airport, it’s got all the tourist and visitor infrastructure and they are building a high-speed train to Bangkok, so it actually meets many criteria,” the source said.

On the downside, a Pattaya integrated resort would almost certainly kill off the casino industry in Poipet, which would undoubtedly stir up rapid opposition from powerful people in the Cambodian border town.

Similar issues would likely face any such development in Bangkok, where the underground casinos are controlled, some say, “at a very, very high level.”

Although far removed from the glitzy casino floors of Asia’s integrated resorts, these often elaborate setups have been estimated to generate more than US$5.5 billion in revenue annually and are alleged to operate under the protection of authorities, who are paid substantial monthly protection fees to provide tip-offs whenever a raid is imminent.

While any moves to create a regulated casino industry may meet with substantial resistance from those who profit from the current status quo, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

“Thailand is a very ‘top down’ country, so if the King says ‘This is going to happen and everyone must fall in line,’ then it can happen, although clearly there would be a lot of people opposed to having a legal casino,” one source explains.

“At the same time, the people running the underground casinos are almost a different market. If there was an entry fee [at the IRs] to keep out locals who shouldn’t be gambling, that’s the market for underground casinos right there, because they don’t care.

“As long as [the IR is] not in Bangkok then they could still profit from their illegal businesses.”

Proponents of legalizing casino gambling in Thailand present some strong arguments. In part due to COVID-19 decimating the tourism sector – which the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council said contributed around 20% of Thailand’s GDP in 2020 – the Thai government has borrowed around THB1.5 trillion (US$46.4 billion) since the start of the pandemic, pushing the total public debt to its highest level in 21 years at over THB9.6 trillion (US$297 billion), equal to 58.3% of GDP.

At the same time, the quality of tourists visiting Thailand, measured by average tourist spend, has been falling compared with some of its regional neighbors.

“They have needed something for some time to make Thailand more competitive,” a source said.

Opposition to casinos, apart from that voiced by the powerful Buddhist religion, is also less vocal in Thailand than in places like Indonesia and Japan. Despite polls showing more people oppose than support casino development, a 2019 study by the Center for Gambling Studies found that 57% of the population had gambled at least once in the previous 12 months.

Yet for all of this, those IAG heard from – most speaking on condition of anonymity – universally said regulated casino gaming in Thailand remains long odds to become a reality.

I’m fairly cynical,

said one highly experienced commentator.

“I just can’t see them achieving what they need to achieve. Too many snouts in the trough, too many vested interests. I don’t see a clean, properly regulated gaming industry in Thailand.

“I think there is a great opportunity there but I suspect the Thais will miss that opportunity, just like the Japanese have. There would be too many people wanting a piece of the action. If they went about it the right way they could have a fantastically successful industry here but I’m cynical about them getting it right.”

Umansky is even more forthright. he said;

There is really no reason to look at Thailand – it’s a giant waste of time.

Umansky

“Could it be a good casino market? Yeah, depending on how it’s structured. As with all things gaming it depends upon the regulatory environment and the tax structure and what you can and can’t do, what you need to invest, and that will determine whether it makes any sense.

- Suggested read: STANLEY HO: how love life shaped his success.

“We’ve gone to numerous jurisdictions where they have had delusions of creating a Macau, when it’s not feasible to do so because they are not Macau, so they have either hoodwinked a bunch of investors or created a bunch of noise and nothing has come out of it.

“Thailand isn’t that severe because I don’t think they have ever given anyone the impression that anyone should do any real work in Thailand, but if the government decided to do something it would take a very, very long time and I’m skeptical over their ability to get the law and industry structure right from the perspective of it making any sense, even if they proceed.”

“I don’t think so,” replied another industry veteran when asked his thoughts on legal casino gaming in Thailand.

“At the end of the day, I just don’t see a good reason to do so. Here’s a country that already attracts 40 million tourists per year and has everything you could want in the way of tourism, except for casino gaming. Is casino gaming really going to bring that much more benefit or is it going to hurt? I would suggest the latter.”